What a fantastic story it wound up being. I've often remarked to my wife that I wish the world was large again, where cultures remained in somewhat isolation of one another. Where you could travel to the other side of the world and find traditional dress and customs in tact, with no signs of Western dress, music, food, etc. It bothered me a little when I went to Amsterdam on my first trip to Europe and found the Dutch to speak English so well, almost American sounding, see the same crap music on TV, see McDonalds and all the other stores I'm accustomed to seeing on the East Coast of the US. I felt that if it weren't for the canals and architecture, I could have been in any US city. Having gone to Germany and couple times after this I can say that I definitely felt like I was in Germany at all times and loved that , but that's another story. Reading Peking to Paris, you're presented with a world that may as well have existed 500 years ago. People were afraid of cars, some thinking them to be some kind of animal being piloted by demons (at least during the parts occurring in China, Mongolia, and Siberia). Cultures remained so different from one another, and there was no google, GPS, or auto translators to help along the way. News came by telegram, when it existed, not instantaneously via email. To really appreciate this, pick up the book and give it a read, I can't do it enough justice in my brief blog entry.

Now, about the race:

The concept of the race came about in a Paris Newspaper (Le Matin) as a a means of proving the durability of the newfound automobile:

"What needs to be proved today is that as long as a man has a car, he can do anything and go anywhere. Is there anyone who will undertake to travel this summer from Peking to Paris by automobile?"

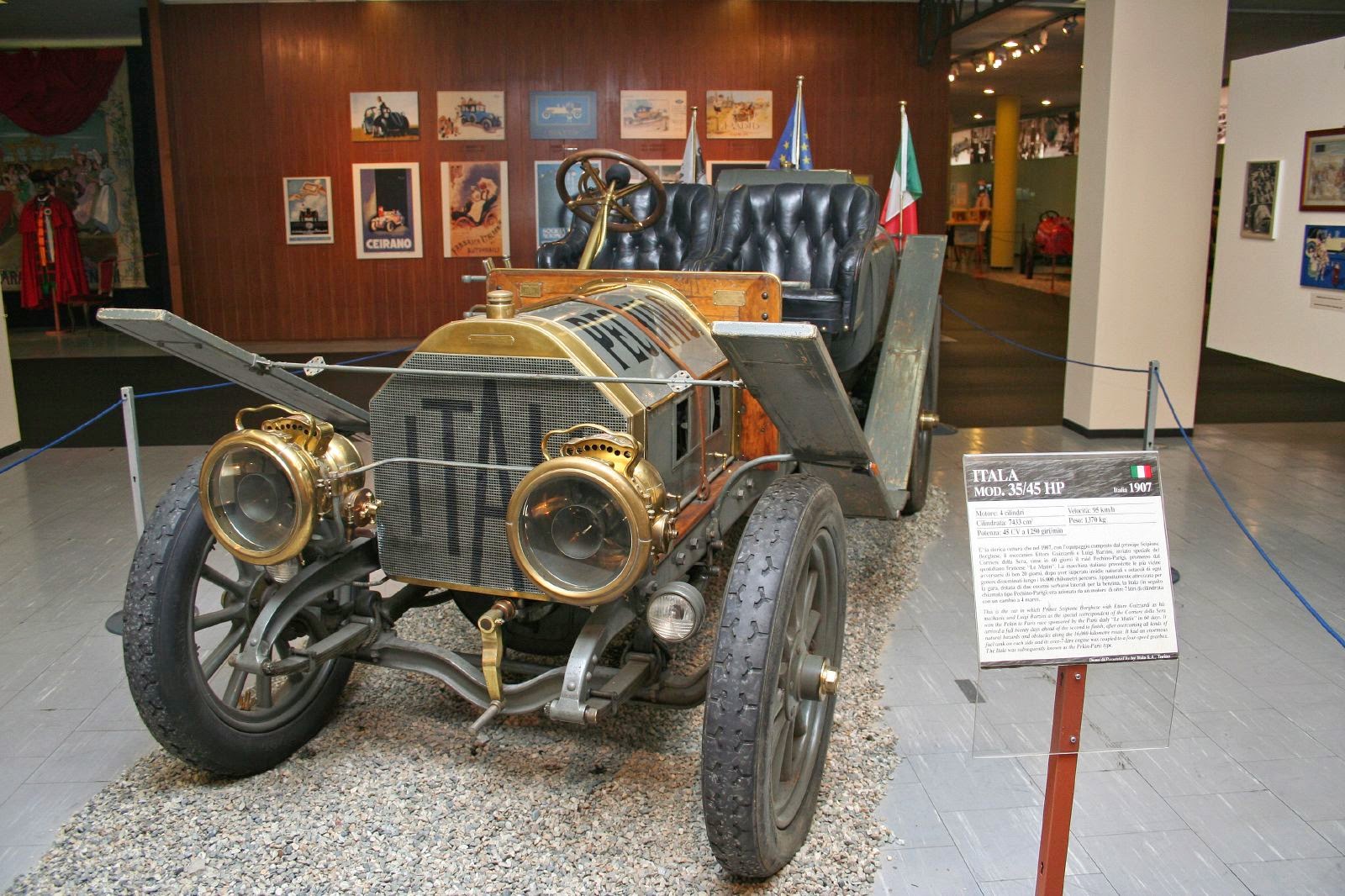

Of 40 entrants, only 5 teams actually committed to the race by providing a deposit and shipping their vehicles to Peking. Due to the vast disparity between original entrants and actual participants, the race was going to be called off, though Prince Borghese (heading the Itala team with his mechanic/chauffeur Ettore Guizzardi) refused to accept the cancellation and sent a telegram to Paris stating his intentions to go to Peking to participate no matter what. His team was joined by a journalist, Luigi Barzini, who was sent by an Italian newspaper to document the race. The other teams consisted of a Dutch team using a Spyker (finishing 2nd), 2 French teams driving DeDions, and another French team using a Contal three-wheeler cycle-car (the only participant not to complete the race).

The Itala 7.0 liter 4-cylinder. Unlike the DeDions this car used a driveshaft instead of chains to power the wheels.

The Itala not only won the race, it did so by a margin greater than a week. During the race it was pulled by coolies through the hills of China, sunk in mud due to the complete absence of roads, and even flipped over and fell due to a bridge collapsing under it . Yet in all instances human power was able to free the machine and put it back on course. At one point a carriage maker built the team a new front wheel, and another made them new leaf springs. With all of our modern conveniences, I don't think my car would fare nearly as well.

The introduction to the book claims that Barzini's story was a standard gift to Italian children graduating school. I guess to supply them with an adventurous spirit, or maybe to keep alive a 20th century Italian triumph. I really think that this sort of tradition should continue, especially over in the US. Here it seems like we're too caught up in playing victims about things, harping on social struggles (real or imagined), obsessed with a world focus, but with no idea of what our own culture really is. Our culture is obsessed with our shortcomings and failures and none of our triumphs.

Our kids need to read about something nice like this, about going on adventures into the unknown, about ingenuity and hardiness conquering every setback. Like I said earlier, I really wish the world was big again, we're so connected to everything nowadays that we have no concept of who we even are anymore.